Nutrition and Management-Related Colic in Horses

The incidence of colic in the general horse population has been estimated between 10 and 11% per year. In a recent study, colic was second only to old-age as the leading cause of death in horses.

The term “colic” strikes fear among horse owners. Colic is a generic term that refers to abdominal pain that can result from many different causes. Among domesticated horses, colic is a major cause of premature death. The incidence of colic in the general horse population has been estimated between 10 and 11% per year. In a recent study, colic was second only to old-age as the leading cause of death in horses.

Most colic problems involve the gastrointestinal tract. Colic symptoms have been associated with composition of diet, changes in diet, feeding practices, exercise patterns, housing and inappropriate parasite control programs. With nutrition related disorders being the top 3 causes of colic in otherwise healthy horses, we should consider our horses' feeding program carefully.

Composition of the Diet

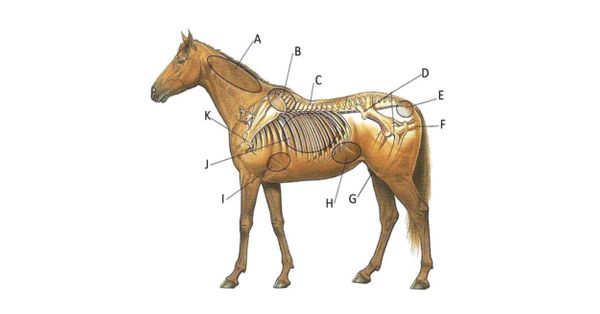

Carbohydrates are the primary source of energy in the horses' diet. Horses evolved to digest forages high in structural carbohydrates (fiber) through bacterial fermentation in a highly developed large intestine. However, the energy needs of performance horses, pregnant and lactating mares and even young, growing horses are higher than the calories supplied by a forage only diet. To meet this increased energy demand, horses are commonly fed more energy dense feedstuffs such as grain concentrates. Grain is rich in starch and sugar, and unlike forage it is digested with enzymes secreted in the small intestine. Surveys have indicated that horses fed large single grain meals, or large volumes of grain throughout the day are more likely to colic with the primary cause due to the limited capacity of the small intestine to digest grain.

Research has shown that small volumes of grain (starch) are digested at a rate of approximately 80 % in the small intestine. If the amount of starch is increased then the small intestine becomes overwhelmed and the excess starch flows into the hind gut where it upsets the microbial population and decreases the pH, resulting in hindgut disruptions and colic. No more than 4- 5 lbs of grain should be fed in a single meal to a 1000 lb horse.

Dietary Changes

An association between feeding practices and disturbances in gut function has long been recognized. Studies have shown that dietary changes, particularly a change in amount of grain fed contributes to an increased risk for colic. Research has also listed changes in batch of hay or type of hay as potential risks for colic.

Therefore all dietary changes should be made gradually over a 2-week adjustment period. An abrupt change in type of forage fed or an increase in the amount of grain will result in an increased rate of fermentation and noticeable changes in the microbial population, and acidity in the hind gut. With a sudden increase in grain, a portion of the sugar and starch passes into the cecum undigested, where it causes gastric disturbances. These disturbances to the hindgut environment put the horse at greater risk for colic, diarrhea, and laminitis. Situations to avoid include (1) a sudden introduction to grain feeding or an abrupt increase in the amount of grain concentrate; (2) the feeding of large grain meals that overwhelm the capacity of the small intestine; and (3) rapid changes in the amount, batch or type of hay being fed.

Housing, Management and Exercise

Housing conditions can influence the risk for colic: horses maintained outside all year long are less susceptible to colic than horses living indoors. Horses that live indoors typically get less exercise and are more likely to accumulate gas within their digestive system compared to horses freely exercising outside. Further, a change in housing is often associated with a change in diet further influencing the likelihood of colic. No association has been found between colic and the type of bedding used. However, impaction colic can occur if horses are bedded on straw and consume large volumes of this non-digestible fiber when not given free access to a more digestible fiber source (e.g. hay, forage cubes etc.). Any large changes in the exercise pattern can cause stress to the animal and bring about colic. When starting a horse's training program or bringing them back into work after a break, make sure all changes in their exercise intensity and frequency are done gradually. Horses that fall into high-risk categories, such as stabled horses in intense training and fit horses recently injured, should be monitored particularly closely. Horses should be allowed as much turnout as possible and owners should maintain a regular feeding schedule. Constant access to an abundant source of clean fresh water is imperative to the avoidance of colic. Care should also be taken not to feed moldy or spoiled grain or hay. As with the diet, make any housing, management, and exercise changes gradually.

Research Update: Feeding Your Horse after Colic

The nutritional requirements of horses after colic surgery or other gastrointestinal illnesses have not been determined. Primary considerations include requirements for energy (calories) and protein. In most situations, the energy requirement for a healthy adult horse at a maintenance level of activity can be met if the horse consumes between 1.5% and 2.5% of its BW per day in hay. However, the energy needs of hospitalized horses are probably much lower because of reduced energy expenditure. When energy supply from carbohydrates and fat in the diet is limited, muscle protein will be used for energy contributing to a loss of lean body mass. Therefore, in developing a nutritional plan, first ensure that minimal energy needs are being met and then ensure the protein requirements are met.

Horses with simple colic (i.e., no specific diagnosis) rarely need special dietary management. Feed and water should be withheld during the colic episode, with resumption of normal feeding after the colic signs have resided. An evaluation of diet may be indicated when there is suspicion that diet or feeding practice contributed to the episode of colic. Some recommend the withholding of grain feedings for a few days to limit gas production in the hindgut. Horses recovering from intestinal surgery can resume feeding when there is clinical evidence of intestinal motility. Initially, the horse should be fed small amounts (1 lb) of good quality forage (e.g., grass hay, alfalfa) four to six times daily, with a gradual increase in the volume of feedings over the following days, providing the horse tolerates the increase in feeding. Alternatively, the horse may be allowed to graze pasture for 20–30 min several times throughout the day or provided a highly digestible; low-bulk pelleted feed such as senior feeds. Grains should be avoided for at least 10–14 days post-surgery (or colic) because of concern that an excess of starch may disrupt an already disrupted hindgut microbial community.

Small Intestinal Disorders

Disorders of intestinal motility are of primary concern after small intestinal surgery. Fresh grass (hand grazing) and mashes or slurries made from alfalfa pellets or pelleted complete feeds are suitable feedstuffs. Molasses may be added to the mash or slurry to enhance palatability of the ration. Small meals (1lb) should be fed every 3–4 hours, again in an effort to minimize physical stress at the surgery site. In uncomplicated cases there should be a gradual introduction to long-stem hay after 3–4 days of soft diet feeding. Bran mashes are not recommended for horses during the early phases of recovery from small intestinal surgery because of the adverse effects of high bulk feeds on the healing of incision sites.

Large Intestinal Disorders

Horses with impaction of the large intestine should not be fed until after resolution of the impaction. Fresh grass, alfalfa pellets, chopped alfalfa hay, and other sources of highly digestible fiber are preferred. Diarrhea is a complication of all types of colic surgery, but the risk seems to be highest in horses undergoing surgery for large intestinal disorders. Horses fed grass hay were half as likely to develop severe diarrhea as horses not fed grass hay. Horses should be fed small amounts of grass or soft grass hay at frequent intervals (every 2–3 hours) as early as 12 hours post-surgery, providing there is no evidence of complications. First cut hay is preferred because of higher dry matter digestibility compared with more mature forages. No grain or concentrate should be introduced until 10–14 days post-surgery. However, the feeding of a low bulk pelleted feed may be beneficial during this period. If additional calories are needed for weight maintenance, a “fat and fiber” concentrate rather than grain or sweet feed is recommended.

After your horse has been treated for colic it is important to monitor signs carefully. Note attitude, water intake, passage of manure (consistency and amount) and gas, urination, gut sounds, gum color (pink is normal), hydration (check gum moisture and skin pinch on point of shoulder), and temperature (less than 101.5 F). Look for any signs of discomfort such as pawing at the ground, looking or kicking at the belly, a distended or tucked-up abdomen, lying down frequently or rolling.

Most horses drink 8-10 gallons of water per day during the summer and 6-8 gallons during the winter. Horses that colic usually have a reduced water intake that may last several days. Warm, clean water should be provided for your horse - if the horse does not drink, try providing a bucket of flavored water in addition to the bucket of fresh water. You can flavor a five gallon bucket with 2 tablespoons salt, 1/8 cup of molasses or 1 can frozen apple juice concentrate or carrot juice or Gatorade.

Geor, R.J. 2007. How to Feed Horses Recovering from Colic. AAEP Proceedings. Pp 196.

Contact your Poulin Grain Feed Specialist to test your hay quality and build a personalized diet for your horse.

www.PoulinGrain.com | 800.334.6731